Adult mental health services

3.89. The Long Term Plan makes a renewed commitment to grow investment in mental health services faster than the NHS budget overall for each of the next five years. The NHS in England is already meeting the goal set in the recently launched Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health that high income countries should be spending at least 10% of their health services budget on mental health [144], and NHS England will be the only major Western health service to have made and sustained such a funding pledge for what will have been eight years by 2023/24. NHS England’s renewed pledge means mental health will receive a growing share of the NHS budget, worth in real terms at least a further £2.3 billion a year by 2023/24. As a result mental health investment will be growing faster over the next five years than over the past five years. It is also the ‘floor’ level of uplift now being set nationally, and we expect it will be further increased by local investment decisions. We will ensure this translates into additional funding for frontline services, including locally agreed spending and delivery plans signed-off by commissioners and providers.

Common disorders

3.90. Nine out of ten adults with mental health problems are supported in primary care. The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme to treat common mental health conditions is world-leading. Mental illness is a leading cause of disability in the UK [145]. Stress, anxiety and depression were the leading cause of lost work days in 2017/18 [146]. The cost of poor mental health to the economy as a whole is estimated to be far in excess of what the country gives the NHS to spend on mental health. So reducing the impact of common mental illness can also increase our national income and productivity [147].

3.91. The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health set out plans for expanding IAPT services so at least 1.5 million people can access care each year by 2020/21. We will continue to expand access to IAPT services for adults and older adults with common mental health problems, with a focus on those with long-term conditions. IAPT services have now evolved to deliver benefits to people with long-term conditions, providing genuinely integrated care for people at the point of delivery. More than half of patients who use IAPT services are moving to recovery, and nine out of ten people now start treatment in less than six weeks [148]. By 2023/24, an additional 380,000 adults and older adults will be able to access NICE-approved IAPT services.

3.92. The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health also set new waiting time standards covering the NHS’ IAPT services, early intervention in psychosis and children and young people’s eating disorders. All of these standards are being achieved or on track for delivery in 2020/21. Alongside work to explore the effectiveness of different approaches to integrated delivery with primary care, we will test four-week waiting times for adult and older adult community mental health teams, with selected local areas. This will help build our understanding of how best to introduce ambitious but achievable improvements in access, quality of care and outcomes. We will then set clear standards for patients requiring access to community mental health treatment and roll them out across the NHS over the next decade.

Severe mental health problems

3.93. The life expectancy of people with severe mental illnesses can be up to 20 years less than the general population. An independent review of the Mental Health Act, chaired by Professor Sir Simon Wessely has now made recommendations on improving legislation and practice [149]. It has examined rising detention rates, racial disparities in detention and concerns that the Act is out of step with a modern mental health system. The government is now considering the findings of the review in detail, including the need for better crisis services and improved community care for people with serious mental illness. Investment in these services forms a major part of this Long Term Plan.

3.94. New and integrated models of primary and community mental health care will support adults and older adults with severe mental illness. A new community-based offer will include access to psychological therapies, improved physical health care, employment support, personalised and trauma-informed care, medicines management and support for self-harm and coexisting substance use. This includes maintaining and developing new services for people who have the most complex needs and proactive work to address racial disparities.

Local areas will be supported to redesign and reorganise core community mental health teams to move towards a new place-based, multidisciplinary service across health and social care aligned with primary care networks. By 2023/24, new models of care, underpinned by improved information sharing, will give 370,000 adults and older adults greater choice and control over their care, and support them to live well in their communities.

Emergency mental health support

3.95. We will expand services for people experiencing a mental health crisis. Three years ago, only 14% of adults surveyed felt they were provided with the right response when in crisis, and only half of community teams were able to offer an adequate 24-hour, seven-day crisis service [150]. In 2016, only 12% of hospital A&E departments had an all-age mental health liaison service meeting the ‘core 24’ service standard [151].

3.96. The NHS will ensure that a 24/7 community-based mental health crisis response for adults and older adults is available across England by 2020/21. Services will be resourced to offer intensive home treatment as an alternative to an acute inpatient We are also working to ensure that no acute hospital is without an all-age mental health liaison service in A&E departments and inpatient wards by 2020/21, and that at least 50% of these services meet the ‘core 24’ service standard as a minimum. By 2023/24, 70% of these liaison services will meet the ‘core 24’ service standard, working towards 100% coverage thereafter.

3.97. In the next ten years we are committed to ensuring the NHS will provide a single point of access and timely, universal mental health crisis care for everyone. We will ensure that anyone experiencing mental health crisis can call NHS 111 and have 24/7 access to the mental health support they need in the community and we will set clear standards for access to urgent and emergency specialist mental health care. This will include post-crisis support for families and staff who are bereaved by suicide, who are likely to have experienced extreme trauma and are at a heightened risk of crisis themselves.

3.98. We will also increase alternative forms of provision for those in crisis. Sanctuaries, safe havens and crisis cafes provide a more suitable alternative to A&E for many people experiencing mental health crisis, usually for people whose needs are escalating to crisis point, or who are experiencing a crisis, but do not necessarily have medical needs that require A&E admission. They are commissioned through the NHS and local authorities, provided at relatively low costs, high satisfaction, and usually delivered by voluntary sector partners. While these services now exist in a number of areas, we will work to improve signposting, and expand coverage to reach more people and make a greater impact.

3.99. Models such as crisis houses and acute day care services, host families and clinical decision units can also prevent admission. The NHS will work hand in hand with the voluntary sector and local authorities on these alternatives and ensuring they meet the needs of patients, carers and families.

3.100. The Clinical Review of Standards will make recommendations for embedding urgent and emergency mental health in waiting time standards. This means that everyone who needs it can expect to receive timely care in the most appropriate setting, whether that is through NHS 111, accessing a liaison mental health service in A&E, or a community-based crisis service. Specific waiting times targets for emergency mental health services will for the first time take effect from 2020.

3.101. Ambulance staff will be trained and equipped to respond effectively to people in a crisis. Ambulance services form a major part of the support people receive in a mental health emergency. For example, South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust reports that at least 10-15% of all calls are related to mental health. We will introduce new mental health transport vehicles to reduce inappropriate ambulance conveyance or by police to A&E. We will also introduce mental health nurses in ambulance control rooms to improve triage and response to mental health calls, and increase the mental health competency of ambulance staff through an education and training programme. A six-month pilot in the Yorkshire Ambulance Service NHS Trust showed that 48% of mental health calls were usually conveyed to A&E, but only 18% when triaged by a mental health nurse.

Inpatient care

3.102. For people admitted to an acute mental health unit, a therapeutic environment provides the best opportunity for recovery. Purposeful, patient-orientated and recovery-focused care is the goal from the outset. Units operating beyond capacity may struggle to offer such care and cannot admit new patients, who are then looked after further away from home or in non-specialist settings. The recent Crisp Commission highlighted a wide variation in the quality and capability of these acute mental health units across the country [152]. The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health programme is working to eliminate inappropriate out of area placements for non-specialist acute care by 2021. We will work with those units with a long length of stay and look to bring the typical length of stay in these units to the national average of 32 days. This will contribute to ending acute out of area placements by 2021, allowing patients to remain in their local area – maintaining relationships with family, carers and friends. In addition, as recommended by Professor Sir Simon Wessely’s Mental Health Act review, capital investment from the forthcoming Spending Review will be needed to upgrade the physical environment for inpatient psychiatric care [153].

Suicide prevention

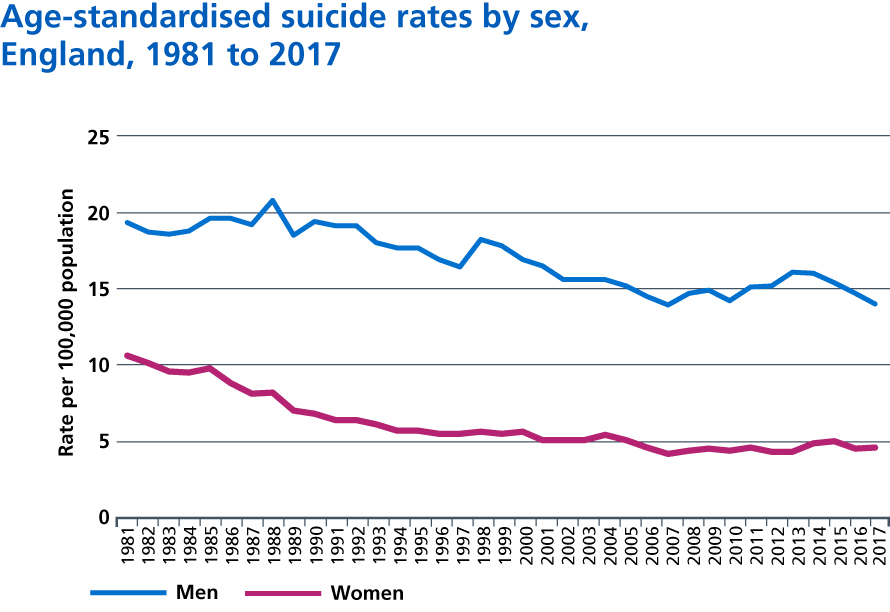

3.103. Since 2015, the suicide rate has reduced from 10.1 to 9.2 per 100,000 of the population, but certain groups of people remain at heightened risk. Suicide is more common in men than women, though male suicide rates are now at their lowest rates in over 30 years, and considerably lower than many other comparable countries.

Figure 20: Age-standardised suicide rates by sex, England, 1981 to 2017.

3.104. The multi-agency suicide prevention and reduction programme implemented as part of the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health was the first of its kind. As part of this programme, we are on track to deliver a 10% reduction in suicide rates by 2020/21 and all local areas across the country now have multi-agency suicide prevention plans in place. We also now have a dedicated quality improvement programme to implement the findings from the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health, and learn from deaths in NHS settings, to prevent future suicides.

3.105. We will continue to build on this progress with the Long Term Plan, so that reducing suicides will remain an NHS priority over the next decade. With the support of partners in addressing this complex, system-wide challenge, we will provide full coverage across the country of the existing suicide reduction programme. Through an enhanced mental health crisis model, anyone experiencing a crisis will be able to call NHS 111 and have 24/7 access to mental health support as well as the services described earlier in this chapter. We will expand specialist perinatal mental health services so that more women who need it have access to the care they need from preconception to two years after the birth of their baby. We are investing in specialist community teams to help support children and young people with autism and their families, and integrated models of primary and community mental health care which will support adults with severe mental illnesses, and support for individuals who self-harm.

3.106. We will design a new Mental Health Safety Improvement Programme, which will have a focus on suicide prevention and reduction for mental health inpatients. Building on the model used in Cambridge and Peterborough’s crisis pathway, we will put in place suicide bereavement support for families and staff working in mental health crisis services in every area of the country. Finally, building on the work of the Global Digital Exemplar (GDE) programme, we will use decision-support tools and machine learning to augment our ability to deliver personalised care and predict future behaviour, such as risk of self-harm or suicide.

Milestones for mental health services for adults

- New and integrated models of primary and community mental health care will give 370,000 adults and older adults with severe mental illnesses greater choice and control over their care and support them to live well in their communities by 2023/24.

- By 2023/24 an additional 380,000 people per year will be able to access NICE-approved IAPT services.

- By 2023/24, NHS 111 will be the single, universal point of access for people experiencing mental health crisis. We will also increase alternative forms of provision for those in crisis, including non-medical alternatives to A&E and alternatives to inpatient admission in acute mental health pathways. Families and staff who are bereaved by suicide will also have access to post- crisis support.

- By 2023/24, we will introduce mental health transport vehicles, introduce mental health nurses in ambulance control rooms and build mental health competency of ambulance staff to ensure that ambulance staff are trained and equipped to respond effectively to people experiencing a mental health crisis.

- Mental health liaison services will be available in all acute hospital A&E departments and 70% will be at ‘core 24’ standards in 2023/24, expanding to 100% thereafter.

References

144. Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., Chisholm, D., Collins, P., Cooper, J., Eaton, J., Herrman, H., Herzallah, M., Huang, Y., Jordans, M., Kleinman, A., Medina-Mora, M., Morgan, E., Niaz, U., Omigbodun, O., Prince, M., Rahman, A., Saraceno, B., Sarkar, B., De Silva, M., Singh, I., Stein, D., Sunkel, C & Unuzter, J (2018) The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. The Lancet. 392 (10157), 1553-1598. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X

145. Knapp, M. (ed.), McDaid, D. (ed.) & Parsonage, M. (ed.). (2011) Mental health promotion and mental illness prevention: the economic case. Department of Health. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/ publications/mental-health-promotion-and-mental-illness-prevention-the-economic-case

146. Health and Safety Executive. (2018) Health and safety at work Summary statistics for Great Britain 2018. Available from: http://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/overall/hssh1718.pdf

147. Farmer, & Stevenson, D. (2017) Thriving at Work: a review of mental health and employers. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/thriving-at-work-a-review-of-mental-health-and-employers

148. NHS Digital. (2018) Psychological Therapies: reports on the use of IAPT services, England – September 2018 final, including reports on the IAPT pilots and quarter 2 2018-19 data – NHS Digital. Available from: https://nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/psychological-therapies-report-on-the-use-of-iapt- services/september-2018-final-including-reports-on-the-iapt-pilots-and-quarter-2-2018-19

149. Department of Health and Social Care (2018) Modernising the Mental Health Act – final report from the independent Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/modernising-the-mental- health-act-final-report-from-the-independent-review

150. CQC. (2015) Right here right now. People’s experiences of help, care and support during a mental health crisis. Available from: https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20150611_righthere_mhcrisiscare_ summary_3.pdf

151. Barrett, J., Aitken, and Lee, W. (n.d.) Report of the 3rd Annual Survey of Liaison Psychiatry in England (LPSE-3). Health Education England. Available from: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/ sites/default/files/documents/Report%20of%20the%203rd%20Annual%20Survey%20of%20Liaison%20 Psychiatry%20in%20England%20FINAL.pdf

152. The Independent Commission on Acute Adult Psychiatric Care (2016) Old Problems, New Solutions: Improving Acute Psychiatric Care for Adults in England. Available from: http://media.wix.com/ugd/0e662e_6f7ebeffbf5e45dbbefacd0f0dcffb71.pdf

153. HM Government (2018) The independent review of the Mental Health Act: Interim report. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/703919/ The_independent_Mental_Health_Act_review pdf