Stronger NHS action on health inequalities

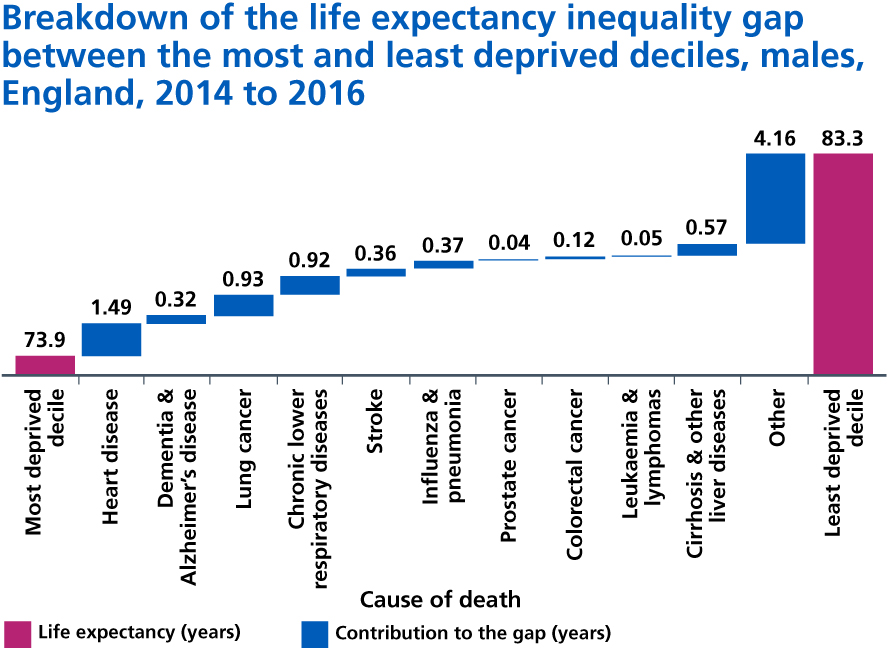

2.23. The NHS was founded to provide universal access to healthcare, though healthcare is only one of many factors that influence our health. The social and economic environment in which we are born, grow up, live, work and age, as well as the decisions we make for ourselves and our families collectively have a bigger impact on our health than health care alone. While life expectancy continues to improve for the most affluent 10% of our population, it has either stalled or fallen for the most deprived 10%. Premature mortality in Blackpool, the most deprived part of the country, is twice as high as in the most affluent areas [44]. Women in the most deprived parts of England spend 34% of their lives in poor health, compared to 17% in the wealthiest areas [45]. Multimorbidity is more common in deprived areas [46], and some parts of our population including BAME communities are at substantially higher risk of poor health and early death. On average, adults with a learning disability die 16 years earlier than the general population – 13 years for men, 20 years for women [47]. People with severe mental health illnesses tend to die 15-20 years earlier than those without [48].

2.24. For reasons both of fairness and of overall outcomes improvement, the NHS Long Term Plan therefore takes a more concerted and systematic approach to reducing health inequalities and addressing unwarranted variation in care. In order to do so and reflecting our Public Sector Equality Duties and other public duties:

2.25. NHS England will continue to target a higher share of funding towards geographies with high health inequalities than would have been allocated using solely the core needs formulae. This funding is estimated to be worth over £1 billion by 2023/24. For the five-year CCG allocations that underpin this Long Term Plan, NHS England will introduce from April 2019 more accurate assessment of need for community health and mental health services, as well as ensuring the allocations formulae are more responsive to the greatest health inequalities and unmet need in areas such as Blackpool. Furthermore, no area will be more than 5% below its new target funding share effective from April 2019, with additional funding growth going to areas between 5% and 2.5% below their target share. NHS England will also commission the Advisory Committee on Resource Allocation to conduct and publish a review of the inequalities adjustment to the funding formulae.

2.26. To support local planning and ensure national programmes are focused on health inequality reduction, the NHS will set out specific, measurable goals for narrowing inequalities, including those relating to poverty, through the service improvements set out in this Long Term Plan. All local health systems will be expected to set out during 2019 how they will specifically reduce health inequalities by 2023/24 and 2028/29. These plans will also, for the first time, clearly set out how those CCGs benefiting from the health inequalities adjustment are targeting that funding to improve the equity of access and outcomes. NHS England, working with PHE and our partners in the voluntary and community sector and local government, will develop and publish a ‘menu’ of evidence-based interventions that if adopted locally would contribute to this goal. We will expect CCGs to ensure that all screening and vaccination programmes are designed to support a narrowing of health inequalities.

2.27. While we cannot treat our way out of inequalities, the NHS can ensure that action to drive down health inequalities is central to everything we do. For example:

2.28. In maternity services, we will implement an enhanced and targeted continuity of carer model to help improve outcomes for the most vulnerable mothers and babies. By 2024, 75% of women from BAME communities and a similar percentage of women from the most deprived groups will receive continuity of care from their midwife throughout pregnancy, labour and the postnatal period. This will help reduce pre-term births, hospital admissions, the need for intervention during labour, and women’s experience of care.

2.29. Women from the most deprived communities are 12 times more likely to smoke during pregnancy than women from more affluent areas. In addition to the enhanced midwife model, we will offer all women who smoke during their pregnancy, specialist smoking cessation support to help them quit.

2.30. People with severe mental illnesses are at higher risk of poor physical health. Compared with the general patient population, patients with severe mental illnesses are at substantially higher risk of obesity, asthma, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cardiovascular disease [49] and make more use of urgent and emergency care [50]. People with a long-standing mental health problem are twice as likely to smoke, with the highest rates among people with psychosis or bipolar disorder. By 2020/21, the NHS will ensure that at least 280,000 people living with severe mental health problems have their physical health needs met. By 2023/24, we will further increase the number of people receiving physical health checks to an additional 110,000 people per year, bringing the total to 390,000 checks delivered each year including the ambition in the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health.

2.31. Over 1.2 million people in England have a learning disability and face significant health inequalities compared with the rest of the population [51],[52]. Autism is a lifelong condition and a part of daily life for around 600,000 people in England. It is estimated that 20-30% of people with a learning disability also have autism [53]. Despite suffering greater ill-health, people with a learning disability, autism or both often experience poorer access to healthcare [54]. In 2017, the Learning Disabilities Mortality Review Programme (LeDeR) found that 31% of deaths in people with a learning disability were due to respiratory conditions and 18% were due to diseases of the circulatory system. Across the NHS, we will do more to ensure that all people with a learning disability, autism, or both can live happier, healthier, longer lives. This means that we will provide timely support to children and young people and their families. We will do more to keep people well with proactive care in the community. We will ensure that reasonable adjustments are made so that wider NHS services can support, listen to, and help improve the health and wellbeing of people with learning disabilities and autism, and their families. Over the next five years, we will invest to ensure that children with learning disabilities have their needs met by eyesight, hearing and dental services, are included in reviews as part of general screening services and are supported by easily accessible, ongoing care. For people with the most complex needs, we will continue to improve access to care in the community, so that more people can live in or near to their own homes and families. Finally, we will accelerate the LeDeR initiative to identify common themes and learning points and provide targeted support to local areas. Further action on top of this is also set out in Chapter Three.

2.32 The number of people sleeping rough has been increasing in recent years. People affected by homelessness die, on average, around 30 years earlier than the general population [55]. Outside London, where people are more likely to sleep rough for longer, support needs may be 31% of people affected by homelessness have complex needs, and additional financial, interpersonal and emotional needs that make engagement with mainstream services difficult. 50% of people sleeping rough have mental health needs, but many parts of the country with large numbers of rough sleepers do not have specialist mental health support and access to mainstream services is challenging. We will invest up to £30 million extra on meeting the needs of rough sleepers, to ensure that the parts of England most affected by rough sleeping will have better access to specialist homelessness NHS mental health support, integrated with existing outreach services.

Case study

UCLH Pathway Programme

University College London Hospitals has developed the Pathway Programme for homeless patients admitted to hospital. It involves in-hospital GPs and dedicated Pathway nurses working with others to address the housing, financial and social issues of patients. Following its introduction, A&E attendances by supported individuals fell by 38% with a 78% reduction in bed days [56]. Pathway, now a charity, helps the NHS to create hospital teams to support homeless patients and ten hospitals in London, Leeds, Bradford, Manchester and Brighton have since adopted the model [57].

2.33. We will continue to identify and support carers, particularly those from vulnerable communities. Carers are twice as likely to suffer from poor health compared to the general population, primarily due to a lack of information and support, finance concerns, stress and social isolation. Quality marks for carer-friendly GP practices, developed with the Care Quality Commission (CQC), will help carers identify GP services that can accommodate their needs. We will encourage the national adoption of carer’s passports, which identify someone as a carer and enable staff to involve them in a patient’s care, and set out guidelines for their use based on trials in Manchester and Bristol. These will be complemented by developments to electronic health records that allow people to share their caring status with healthcare professionals wherever they present.

2.34. Carers should not have to deal with emergencies on their own. We will ensure that more carers understand the out-of-hours options that are available to them and have appropriate back-up support in place for when they need it. Up to 100,000 carers will benefit from ‘contingency planning’ conversations and have their plans included in Summary Care Records, so that professionals know when and how to call those plans into action when they are needed.

2.35. Young carers feel say they feel invisible and often in distress, with up to 40% reporting mental health problems arising from their experience of caring. Young Carers should not feel they are struggling to cope on their own. The NHS will roll out ‘top tips’ for general practice which have been developed by Young Carers, which include access to preventive health and social prescribing, and timely referral to local support services. Up to 20,000 Young Carers will benefit from this more proactive approach by 23/24.

2.36. We will invest in expanding NHS specialist clinics to help more people with serious gambling problems. Over 400,000 people in England are problem gamblers and two million people are at risk, but current treatment only reaches a small number through one national clinic. We will therefore expand geographical coverage of NHS services for people with serious gambling problems, and work with partners to tackle the problem at source.

2.37. The NHS will continue to commission, partner with and champion local charities, social enterprises and community interest companies providing services and support to vulnerable and at-risk groups. These organisations are often leading innovators in their field. Many provide a range of essential health, care and wellbeing services to groups that mainstream services struggle to reach. Of 100,000 social enterprises in the UK, 31% work in the 20% most deprived communities [58], creating jobs and filling gaps in support as well as addressing wider determinants of health and wellbeing such as debt and housing. For example, Bevan Healthcare, a social enterprise in Bradford, provides NHS GP services alongside wider support to meet the needs of people who are homeless [59]. Community Catalysts, a community interest company, works with people with long term health and care needs to help them develop and run their own micro community enterprises with over 1,800 enterprises being launched across the country [60]. This kind of innovation will need to be encouraged and supported by ICSs to address health inequalities in their populations.

2.38. A major factor in maintaining good mental health is stable employment. This Plan sets out how the NHS is improving access to mental health support for people in work and our commitment to supporting people with severe mental illnesses to seek and retain employment. As the largest employer in England, we are also taking action to improve the mental health and wellbeing of our workforce and setting an example to other employers.

2.39. As well as moderating growth in demand for healthcare, NHS action on health and health inequalities relieves pressure on other essential public services. Detail of some of these actions supported by this Long Term Plan are set out in the Appendix.

References

49. Public Health England (2018) Severe mental illness (SMI) and physical health inequalities: briefing. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/severe-mental-illness-smi-physical-health-inequalities/severe-mental-illness-and-physical-health-inequalities-briefing

50. Dorning, H., Davies, A. & Blunt, I. (2015) Focus on: People with mental ill health and hospital use. The Nuffield Trust. Available from: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/focus-on-people-with-mental-ill-health-and-hospital-use

51. Mencap (2018) How common is learning disability?. Available from: https://www.mencap.org.uk/learning-disability-explained/research-and-statistics/how-common-learning-disability

52. Hosking, F., Carey, I., Shah, S., Harris, T., DeWilde, S., Beighton, C. & Cook, D. (2016) Mortality Among Adults With Intellectual Disability in England: Comparisons With the General Population. American Journal of Public Health. 106 (8), 1483-1490. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303240

53. Emerson, E. & Baines, S. (2010) The Estimated Prevalence of Autism among Adults with Learning Disabilities in England. Improving Health and Lives: Learning Disabilities Observatory. Available from: http://www.wecommunities.org/MyNurChat/archive/LDdownloads/vid_8731_IHAL2010-05Autism.pdf

54. Lenehan, C. (2017) These are our children. Council for disabled children. Available from: https://www.ncb.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/attachment/These%20are%20Our%20CHildren_Lenehan_Review_Report.pdf

55. Thomas, B. (2012) Homelessness kills: An analysis of the mortality of homeless people in the early twentyfirst century in England. Crisis. Available from: https://www.crisis.org.uk/media/236798/crisis_homelessness_kills2012.pdf

56. Wyatt, L. (2017) Positive outcomes for homeless patients in UCLH Pathway programme. British Journal of Healthcare Management. 23 (8), 367-371. Available from: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjhc.2017.23.8.367

57. Pathway (2018) About us. Available from: https://www.pathway.org.uk/about-us/

58. Social Enterprise UK (2016) What is it all about? Available from: https://www.socialenterprise.org.uk/what-is-it-all-about

59. Bvan Healthcare (2018) About Bevan Healthcare. Available from: https://bevanhealthcare.co.uk/about-us/

60. Community Catalysts (2018) Community enterprise. Available from: https://www.communitycatalysts.co.uk/whatweoffer/communitymicro-enterprise/