1. We will boost ‘out-of-hospital’ care, and finally dissolve the historic divide between primary and community health services

1.5. Community health services and general practice face multiple challenges – with insufficient staff and capacity to meet rising patient need and complexity. GPs are retiring early and newly-qualified GPs are often working part-time. Reform of the GP contract in 2004 improved the quality and income of primary care practitioners, but relative investment in primary care then fell for the rest of the decade before beginning to recover after the creation of NHS England from 2014/15, and then more substantially in 2017/18 and 2018/19. Use of locum GPs has increased and there is shortage of practice and district nurses. The traditional business model of the partnership is proving increasingly unattractive to early and mid-career GPs. Patient satisfaction with access to primary care has declined, particularly amongst 16-25 year olds.

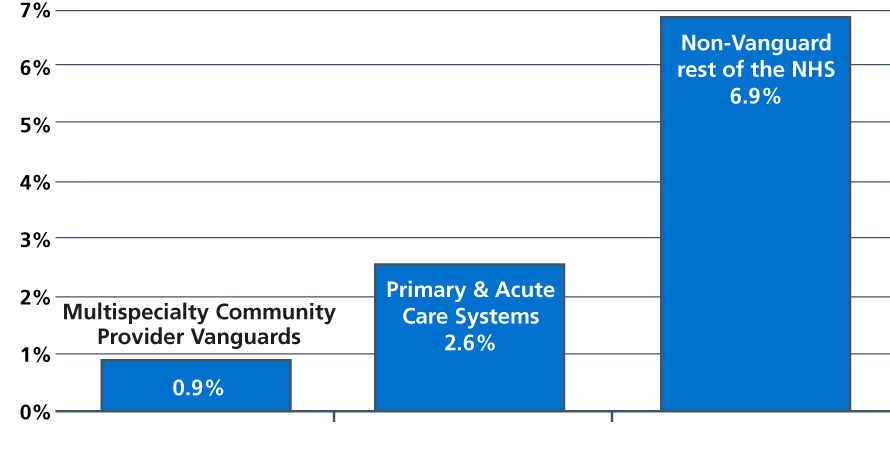

1.6. Following three years of testing alternative models in the Five Year Forward View through integrated care ‘Vanguards’ and Integrated Care Systems, we now know enough to commit to a series of community service redesigns everywhere. The Vanguards received less than one tenth of one percent of NHS funding, but made a positive impact on emergency admissions, and demonstrated the benefits of proactively identifying, assessing and supporting patients at higher risk to help them stay independent for longer.

Figure 1: Growth in emergency admissions per capita 2014/15 to 2017/18: MCP and PACS Vanguards vs. the rest of the NHS.

Note: The MCP and PACS combined emergency growth rate is 1.6% which is statistically significantly lower than the rest of the NHS with 95% CI (the upper limit for a significant value is 3.1%).

Source: NHS England analysis of Secondary Uses Service (SUS) data.

1.7. In this Long Term Plan we commit to increase investment in primary medical and community health services as a share of the total national NHS revenue spend across the five years from 2019/20 to 2023/24. This means spending on these services will be at least £4.5 billion higher in five years time. This is the first time in the history of the NHS that real terms funding for primary and community health services is guaranteed to grow faster than the rising NHS budget overall. And this is a ‘floor’ level of investment that is being nationally guaranteed, that local clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and ICSs are likely to supplement further. This investment guarantee will fund demand pressures, workforce expansion, and new services to meet relevant goals set out across this Plan.

A new NHS offer of urgent community response and recovery support

1.8 Over the next five years all parts of the country will be asked to increase the capacity and responsiveness of community and intermediate care services to those who are clinically judged to benefit more. Extra investment and productivity reforms in community health services will mean that within five years all parts of the country will be expected to have improved the responsiveness of community health crisis response services to deliver the services within two hours of referral in line with NICE guidelines, where clinically judged to be appropriate. In addition, all parts of the country should be delivering reablement care within two days of referral to those patients who are judged to need it. This will help prevent unnecessary admissions to hospitals and residential care, as well as ensure a timely transfer from hospital to community. More NHS community and intermediate health care packages will be delivered to support timely crisis care, with the ambition of freeing up over one million hospital bed days. Urgent response and recovery support will be delivered by flexible teams working across primary care and local hospitals, developed to meet local needs, including GPs and SAS doctors, allied health professionals (AHPs), district nurses, mental health nurses, therapists and reablement teams. Extra recovery, reablement and rehabilitation support will wrap around core services to support people with the highest needs.

Primary care networks of local GP practices and community teams

1.9. The £4.5 billion of new investment will fund expanded community multidisciplinary teams aligned with new primary care networks based on neighbouring GP practices that work together typically covering 30-50,000 people. As part of a set of multi-year contract changes individual practices in a local area will enter into a network contract, as an extension of their current contract, and have a designated single fund through which all network resources will flow. Most CCGs have local contracts for enhanced services and these will normally be added to the network contract. Expanded neighbourhood teams will comprise a range of staff such as GPs and SAS doctors, pharmacists, district nurses, community geriatricians, dementia workers and AHPs such as physiotherapists and podiatrists/chiropodists, joined by social care and the voluntary sector. In many parts of the country, functions such as district nursing are already configured on network footprints and this will now become the required norm.

1.10. The result will be the creation – for the first time since the NHS was set up in 1948 – of fully integrated community-based health care. This will be supported through the ongoing training and development of multidisciplinary teams in primary and community hubs. Community hospital hubs will play their full part in many of these integrated multidisciplinary teams. From 2019, NHS 111 will start direct booking into GP practices across the country, as well as refer on to community pharmacies who support urgent care and promote patient self-care and self-management. CCGs will also develop pharmacy connection schemes for patients who don’t need primary medical services.

1.11. To support this new way of working we will agree significant changes to the GP Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). This will include a new Quality Improvement (QI) element, which is being developed jointly by the Royal College of GPs, NICE and the Health Foundation. The least effective indicators will be retired, and the revised QOF will also support more personalised care. In 2019 we will also undertake a fundamental review of GP vaccinations and immunisation standards, funding, and procurement. This will support the goal of improving immunisation coverage, using local coordinators to target variation and improve groups and areas with low vaccines uptake.

1.12. We will also offer primary care networks a new ‘shared savings’ scheme so that they can benefit from actions to reduce avoidable A&E attendances, admissions and delayed discharge, streamlining patient pathways to reduce avoidable outpatient visits and over- medication through pharmacist review.

Guaranteed NHS support to people living in care homes

1.13. One in seven people aged 85 or over permanently live in a care home. People resident in care homes account for 185,000 emergency admissions each year and 1.46 million emergency bed days, with 35-40% of emergency admissions potentially avoidable [5]. Evidence suggests that many people living in care homes are not having their needs assessed and addressed as well as they could be, often resulting in unnecessary, unplanned and avoidable admissions to hospital and sub-optimal medication regimes.

1.14. NHS England’s Enhanced Health in Care Homes (EHCH) Vanguards have shown how to improve services and outcomes for people living in care homes and those who require support to live independently in the community. For example, in Nottinghamshire, people resident in care homes within the Vanguard experienced 29% fewer A&E attendances and 23% fewer emergency admissions than a matched control group [6].

1.15. We will upgrade NHS support to all care home residents who would benefit by 2023/24, with the EHCH model rolled out across the whole country over the coming decade as staffing and funding grows. This will ensure stronger links between primary care networks and their local care homes, with all care homes supported by a consistent team of healthcare professionals, including named general practice support. As part of this, we will ensure that individuals are supported to have good oral health, stay well hydrated and well-nourished and that they are supported by therapists and other professionals in rehabilitating when they have been unwell. Care home residents will get regular clinical pharmacist-led medicine reviews where needed. Primary care networks will also work with emergency services to provide emergency support, including where advice or support is needed out of hours. We will support easier, secure, sharing of information between care homes and NHS staff. Care home staff will have access to NHSmail, enabling them to communicate effectively and securely with NHS teams involved in the care of their patients.

Supporting people to age well

1.16. People are now living far longer, but extra years of life are not always spent in good health [7] , as Table 1 shows. They are more likely to live with multiple long-term conditions, or live into old age with frailty or dementia, so that on average older men now spend 2.4 years and women spend three years with ‘substantial’ care needs [8].

Table 1: Life expectancy and proportion of life in poor health, from birth and age 65 years, males and females, largest EU countries, 2016.

| Males | Females | |||||||

| Country | Life expectancy at birth | Proportion (%) in poor health | Life expectancy at age 65 | Proportion (%) in poor health | Life expectancy at birth | Proportion (%) in poor health | Life expectancy at age 65 | Proportion (%) in poor health |

| France | 79.5 | 6.4 | 19.6 | 16.3 | 85.7 | 8.1 | 23.7 | 18.6 |

| Germany | 78.6 | 6.4 | 18.1 | 14.4 | 83.5 | 7.8 | 21.3 | 18.3 |

| United Kingdom | 79.4 | 6.9 | 18.8 | 13.8 | 83.0 | 8.0 | 21.1 | 13.7 |

| EU

average |

78.2 | 6.5 | 18.2 | 17.6 | 83.6 | 8.7 | 21.6 | 23.1 |

Note: Poor health is defined as the difference between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy.

Source: European Statistics (EUROSTAT). Healthy life years and life expectancy at age 65 by sex. 2018.

1.17. Extending independence as we age requires a targeted and personalised approach, enabled by digital health records and shared health management tools. Primary care networks will from 2020/21 assess their local population by risk of unwarranted health outcomes and, working with local community services, make support available to people where it is most needed. GPs are already using the Electronic Frailty Index to routinely identify people living with severe frailty. Using a proactive population health approach focused on moderate frailty will also enable earlier detection and intervention to treat undiagnosed disorders, such as heart failure. Based on their individual needs and choices, people identified as having the greatest risks and needs will be offered targeted support for both their physical and mental health needs, which will include musculoskeletal conditions, cardiovascular disease, dementia and frailty. Integrated primary and community teams will work with people to maintain their independence: for example, 30% of people aged 65 and over, and 50% of those aged 80 and over, are likely to fall at least once a year [9]. Falls prevention schemes, including exercise classes and strength and balance training, can significantly reduce the likelihood of falls and are cost effective in reducing admissions to hospital [10].

1.18. The connecting of home-based and wearable monitoring equipment will increasingly enable the NHS to predict and prevent events that would otherwise have led to a hospital admission. This could include a set of digital scales to monitor the weight of someone post-surgery, a location tracker to provide freedom with security for someone with dementia, and home testing equipment for someone taking blood thinning drugs. Currently available technology can enable earlier discharge from hospital and transform people’s lives if it is connected to their Personal Health Record (PHRs) and integrated into the NHS’ services. We will support advances in these care models over the next five years. To do so requires major work to digitise community services, as set out in Chapter Five. As well as deploying technology to support community staff, we will expand the scope of the existing Community Dataset to standardise information across the care system and integrate it with Local Health Care Records (LHCRs).

1.19. Carers will benefit from greater recognition and support. The latest Census found that 10% of the adult population has an unpaid caring role, equating to approximately 5.5 million people in England – around 4 million of whom provide upwards of 50 hours care per week. 17% of respondents to the GP patient survey identified themselves as carers. Many carers are themselves older people living with complex and multiple long-term conditions. We will improve how we identify unpaid carers, and strengthen support for them to address their individual health needs. We will do this through introducing best-practice Quality Markers for primary care that highlight best practice in carer identification and support.

1.20. We will go further in improving the care we provide to people with dementia and delirium, whether they are in hospital or at home. One in six people over the age of 80 has dementia and 70% of people in care homes have dementia or severe memory problems. There will be over one million people with dementia in the UK by 2025, and there are over 40,000 people in the UK under 65 living with dementia today [11]. Over the past decade the NHS has successfully doubled the dementia diagnosis rate and halved the prescription of antipsychotic drugs [12]. We have continued to improve public awareness [13] and professional understanding. Research investment is set to double between 2015 and 2020, with £300m of government support [14]. We will provide better support for people with dementia through a more active focus on supporting people in the community through our enhanced community multidisciplinary teams and the application of the NHS Comprehensive Model of Personal Care. We will continue working closely with the voluntary sector, including supporting the Alzheimer’s Society to extend its Dementia Connect programme which offers a range of advice and support for people following a dementia diagnosis.

References

5. NHS England internal analysis

6. The Health Foundation (2017) The impact of providing enhanced support for care home residents in Rushcliffe: Health Foundation consideration of findings from the Improvement Analytics Unit. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/publication/impact-enhanced-support-rushcliffe

7. Raleigh, (2018) What is happening to life expectancy in the UK?. The Health Foundation. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/whats-happening-life-expectancy-uk

8. Kingston, A., Wohland, , Wittenberg, R., Robinson, L., Brayne, C., Matthews, F. & Jagger, C. (2017) Is late life dependency increasing or not? A comparison of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Studies (CFAS). The Lancet. 390 (10103), 1676-1684. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31575-1

9. Royal College of Nursing (2018) Falls Resources for nursing professionals on the prevention, treatment and management of falls in older Available from: https://www.rcn.org.uk/clinical-topics/older-people/falls

10. Public Health England (2018) A Return on Investment Tool for the Assessment of Falls Prevention Programmes for Older People Living in the Community. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/679856/A_return_on_investment_tool_for_falls_prevention_programmes.pdf

11. Prince, M., Knapp, M., Guerchet, , McCrone, P., Prina, M., Comas-Herrera, A., Wittenberg, R., Adelaja, B., Hu, B., King, D., Rehill, A. & Salimkumar, D. (2014) Dementia UK: Second edition – Overview. Alzheimer’s Society. Available from: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/59437/1/Dementia_UK_Second_edition_-_Overview.pdf

12. Donegan, K., Fox, N., Black, N., Livingston, G., Banerjee, S. & Burns, A. (2017) Trends in diagnosis and treatment for people with dementia in the UK from 2005 to 2015: a longitudinal retrospective cohort The Lancet Public Health. 2 (3), PE149-E156. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30031-2

13. Alzheimer’s Research UK (2016) Attitudes to dementia. Available from: https://www.dementiastatistics.org/statistics/attitudes-to-dementia/

14. Department of Health (2015) Prime Ministers Challenge on Dementia 2020: Implementation Plan. p.62. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/507981/PM_Dementia-main_acc.pdf